The Charly programming language

This post is the first from our guest writers series. If you have built something awesome using Crystal and want to share your experience here on the blog, let us know!

Today’s guest author is Leonard Schütz. He created the Charly programming language as a means to learn how to create a programming language, and after a first iteration in Ruby, he moved to Crystal to implement the language interpreter. In this post, he presents the language, shows how it works, and why he chose Crystal to implement it.

Introduction

Charly is a dynamically typed and object-oriented programming language. The syntax is mostly inspired by languages like JavaScript or Ruby, but offers more freedom when writing. The first difference one might notice is the absence of semicolons or the missing need for parenthesis in most of the languages control structures. Charly, as it is right now, is just a toy language written in spare time.

How does it look?

Below is an implementation of the Bubblesort algorithm written in Charly. It is part of the standard library which is also written in Charly.

func sort(sort_function) {

const sorted = @copy()

let left

let right

@length().times(->(i) {

(@length() - 1).times(->(y) {

left = sorted[i]

right = sorted[y]

if sort_function(left, right) {

sorted[i] = right

sorted[y] = left

}

})

})

sorted

}

This program prints out the Mandelbrot set in a 60x180 sized box.

60.times(func(a) {

180.times(func(b) {

let x = 0

let y = 0

let i = 0

while !(x ** 2 + y ** 2 > 4 || i == 99) {

x = x ** 2 - y ** 2 + b / 60 - 1.5

y = 2 * x * y + a / 30 - 1

i += 1

}

if i == 99 {

write("#")

} else if i <= 10 {

write(" ")

} else {

write(".")

}

})

write("\n")

})

This link takes you to an expression parser / interpreter written entirely in Charly. It supports the addition and multiplication of integer values.

How does it work?

First, Charly turns the source file into a list of tokens. A token is basically just a string with a type. A simple hello-world program may consist of the following tokens:

$ cat test/debug.ch

print("Hello World")

$ charly test/debug.ch -f lint -f tokens

1:1:5 │ Identifier │ print

1:6:1 │ LeftParen │ (

1:7:13 │ String │ "Hello World"

1:20:1 │ RightParen │ )

1:21:1 │ Newline │

2:1:1 │ EOF │

This part of the program is called the lexer (Lexical Analysis). It turns the source-code into logical groups of characters. For example, the print identifier is now a token of the type Identifier, containing the string print. Same goes for the text which is being printed. It is now a token of the type String, containing the string Hello World.

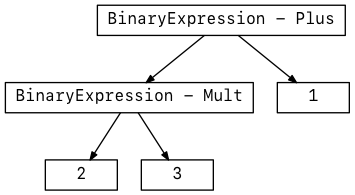

After the whole program was turned into a list of tokens, the parser turns them into an AST (Abstract Syntax Tree). The AST is a way of representing a program as a tree structure. Each node has a type and 0 or more children. The expression 1 + 2 * 3 would produce an AST which looks like this:

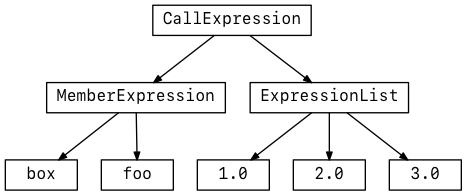

Something more sophisticated such as a method-call on an object might look like this:

Once the whole program has been turned into the AST, the interpreter starts to recursively traverse this structure. This procedure follows the Visitor pattern to separate the AST and language logic.

Take a BinaryExpression as an example. It has three properties. The two values of the expression and an operator.

This operator could be a plus, minus or any other operator the language supports.

It first resolves the two values, checks what operator is being used and applies it to the two values.

Depending on which value is on which side, this procedure might produce completly different results.

3 + [1, 2] is not the same as [1, 2] + 3 (NAN and [1, 2, 3]).

A IdentifierLiteral would load a value from the current scope, a CallExpression would invoke a pre-defined function and so on.

Why Crystal?

The main reasons behind using Crystal for this project were speed and simplicity.

Crystal’s syntax and standard library are both inspired by Ruby. This means you can reuse a lot of knowledge and established principles and practices from the Ruby world, in your Crystal projects. A lot of the API details are pretty similar. For example, if you’re unable to find any information on how to open files in Crystal, you can even google “Ruby open file” and you’ll discover that the first answer on StackOverflow is 100% valid Crystal code. Of course this doesn’t hold up for more complicated things but you can always use it as a place of inspiration.

Another great thing about Crystal is that you don’t have to deal with a lot of low-level stuff. Crystal’s standard library takes care of most things you’d consider low-level, even memory management. If you really need to do low-level stuff, you have access to raw pointers and bindings to C. This is also how the regex literal is implemented in Crystal. Internally it binds to the PCRE Library and places an easy-to-use abstraction over it. Instead of reinventing the wheel, Crystal just binds to already existing C libraries. Crystal also binds to the C standard library, OpenSSL, LibGMP, LibXML2, LibYAML and many others.

Another big reason for switching to Crystal was speed. Crystal is blazingly fast. The old Charly implementation, which used Ruby 2.3, took over 300 milliseconds just to parse a single file. On top of that, it took about 1.8 seconds to run the test suite. The program written in Crystal and compiled with the --release option, took about 1-2 milliseconds to do all of that! Pretty impressive.

Since Crystal uses LLVM, your program runs through all of their optimization passes. These include, but are not limited to: constant-folding, dead-code-elimination, function-inlining and even the evaluation of complete code branches at compile-time. You won’t get that with Ruby ;)

It took me about a week to rewrite most of the interpreter in Crystal, with only small bug fixes and changes to the standard library taking longer than that.

Another great thing about developing in Crystal, is that the compiler itself is also written in Crystal. This means Crystal is self-hosted. There were multiple occasions where I copied code from Crystal’s compiler and adapted it for my own use. Crystal’s parser and lexer for example were really helpful in understanding how these things work (I had never written a parser and lexer before).

The Macro System

The Macro system was really handy in a lot places. It was mainly used to avoid boilerplate and to follow the DRY pattern.

For some real examples of how the Macro system could be used, look at these files:

Crystal’s standard library for example, uses macros to provide the property method. You can use it to avoid boilerplate when introducing new instance variables to your classes.

Conclusion

In it’s current state, Charly is just a learning project for myself. At the moment, I wouldn’t recommend using it for anything serious beside as a learning resource on how to write an interpreter yourself. Charly is being developed on GitHub, so feel free to open any issues, propose new features or even send your own pull requests. Feedback in the comments of this article is also greatly appreciated.

I’ve started using Crystal around August 2016 and I’m absolutely in love with it. It is one of the most expressive and rewarding languages I have ever written code in. If you haven’t used Crystal before, you should try it out now.

About the Author

My name is Leonard Schütz, I’m a 16 year old student from Switzerland. I’m currently an apprentice at Siemens in the field of Healthcare, where I work mostly with PHP, EWS and other web technologies. In my spare time I like to work on side-projects, of which the Charly programming language is my current one.

Feel free to follow me on Twitter, GitHub or check out my website at leonardschuetz.ch

Thanks for reading!

Links & Sources

- Leonard Schütz: leonardschuetz.ch

- Charly Programming Language: charly-lang/charly

- GraphViz (used for AST visualisations): www.graphviz.org

- “Ruby open file” on stackoverflow: how-to-read-an-open-file-in-ruby

- Old test suite used for the ruby interpreter: test/main.ch